Imagine this: you’re sitting in a dim café somewhere along the Silk Road. Not the sanitized “Silk Road Experience” from a travel app, but the real thing – chipped teacups, the smell of boiled lamb, and the feeling that anything could happen. Across from you sits a man with eyes like drill bits and the posture of someone who has seen the end of the world and ordered another drink anyway. He leans forward and tells you, in a thick accent, that most people are asleep, and you are one of them. Congratulations.

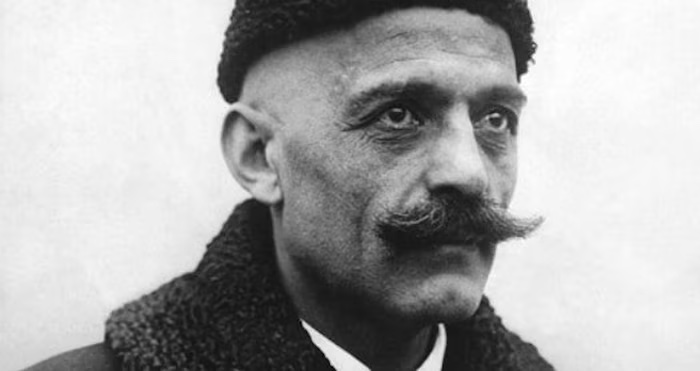

That man could be George Ivanovich Gurdjieff – mystic, hustler, hypnotist, teacher of “The Fourth Way,” and the kind of human puzzle that makes you question your own operating system. Sitting a few seats away might be P. D. Ouspensky, a mathematician-turned-journalist who tried to translate Gurdjieff’s labyrinthine teachings into something the rest of us could understand without blowing a mental fuse.

This is their story, and maybe yours too.

Who Was Gurdjieff?

Gurdjieff was born in the late 19th century in what is now Armenia or possibly Georgia – he wasn’t big on birth certificates. He grew up in a melting pot of cultures, absorbing stories, religions, and languages like a sponge in a whiskey barrel.

From there, he did something most of us say we want to do but never will: he hit the road. For decades. Through Central Asia, the Middle East, Tibet, Egypt, India. Not as a tourist, but as a seeker. He hunted down esoteric schools, ancient monasteries, and scraps of forgotten wisdom like they were rare vinyl records in a flea market.

What came out of those travels wasn’t just a mash-up of religious greatest hits. It was a philosophy of human potential that told people they weren’t fully awake, and that they could be – but only if they worked like hell.

Enter Ouspensky: The Reluctant Interpreter

Ouspensky was a Russian intellectual who, like many of his peers in the early 20th century, was looking for something bigger than vodka and revolution. He met Gurdjieff in Moscow in 1915, and it hit him like a freight train. Here was a man who spoke of cosmic laws, human sleep, and inner transformation with the conviction of someone who had lived it.

But Gurdjieff wasn’t an easy teacher to follow. His explanations could sound like riddles written by a drunken mathematician. Ouspensky took it upon himself to organize, clarify, and publish the ideas — most famously in his book In Search of the Miraculous.

If Gurdjieff was the raw, unfiltered spirit, Ouspensky was the distiller.

The Fourth Way: Not a Monk, Not a Fakir, Not a Yogi

Most spiritual traditions fall into one of three paths:

- The Way of the Fakir: Physical mastery, discipline, sometimes extreme asceticism.

- The Way of the Monk: Faith and devotion as the road to transformation.

- The Way of the Yogi: Mastery of consciousness through meditation and control of mind.

Gurdjieff said there was a fourth option — The Fourth Way — which combines the strengths of all three but can be practiced in the midst of ordinary life. No monastery, no hermitage, no endless yoga retreat.

The key was self-remembering: a heightened state of awareness in which you’re conscious of yourself and your actions in real time. It’s not zoning out into bliss. It’s becoming more aware, not less.

The Law of Seven: Why Life Doesn’t Move in Straight Lines

One of Gurdjieff’s central ideas was the Law of Seven (or the Law of Octaves). Think of it as the anti-momentum law. In nature, nothing goes in a perfect straight line toward completion. Everything proceeds in a series of steps and interruptions, like a musical scale, with its built-in half steps where momentum naturally shifts or stalls.

In practical terms:

- Your new diet? It will hit a wall unless you consciously adjust at the natural “half-step” points.

- That business project? Same thing. Momentum will fade unless you reintroduce energy at key moments.

The takeaway: Expect the stall points. Plan for them. Inject conscious effort when the flow starts to slow. Without that, everything decays.

Meditation, Gurdjieff-Style vs. Buddhist-Style

If Buddhist meditation is about observing thoughts without attachment, Gurdjieff’s method is more like standing on a moving train and learning to keep your balance while taking inventory of the luggage.

Buddhism often seeks stillness and equanimity. Gurdjieff’s approach, especially in his “Movements” and self-remembering exercises, seeks active awareness, not quieting the mind, but sharpening it while fully engaged with life.

His “sittings” involved focusing on bodily sensations, posture, breath, and the presence of attention in different parts of the body — all while maintaining the sense of “I am here.” It’s less “become the mountain” and more “notice every stone in the path while still walking.”

Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson

This is Gurdjieff’s magnum opus, and it’s not an easy ride. Written in dense, almost alien prose, it’s framed as Beelzebub telling his grandson about the follies and misadventures of humanity. It’s allegory, satire, spiritual critique, and cosmic mythology all rolled into one.

The book’s stated goal was to make readers think for themselves — even to struggle — so that understanding wasn’t spoon-fed but earned. If you pick it up, expect to reread sentences three times and still feel like you’re deciphering an encrypted telegram.

In Search of the Miraculous

If Beelzebub’s Tales is the mountain, In Search of the Miraculous is the trail map. Written by Ouspensky, it distills Gurdjieff’s main teachings into something far more readable. It covers the nature of human “sleep,” the idea of mechanical behavior, the structure of the cosmos, and the possibility of awakening through the Fourth Way.

It’s a good starting point for anyone who wants the meat of Gurdjieff without the full esoteric banquet.

Practical Ways to Apply Gurdjieff’s Ideas Today

1. Practice Self-Remembering Daily

Imagine standing in line for coffee. Instead of scrolling your phone, notice your breath, the weight of your feet, your surroundings, and the fact that you are here, now. Hold that awareness for 30 seconds. Then try a minute. It’s surprisingly hard.

2. Work Against Automaticity

Notice when you’re on autopilot: driving, walking, typing. Break the pattern by introducing conscious action: change your route, use your non-dominant hand, pause before speaking.

3. Use the Law of Seven

Identify natural stall points in any project or habit. Schedule a deliberate change or renewed effort at those points. Treat momentum like a fire, it needs stoking.

4. Seek Multiple Lines of Development

Don’t just hit the gym or just read philosophy. The Fourth Way says develop body, emotions, and intellect together. Rotate through practices that challenge all three.

5. Make Struggle Productive

If you feel resistance in a task, don’t just push through blindly. Ask: Is this a stall point? Do I need a new input? Or am I asleep at the wheel?

Pull Quotes & Callouts

“Man is a machine, but a machine that can know it is a machine.”

“Without conscious effort, everything runs downhill.”

“To awaken is not to escape the world, but to engage with it fully aware.”

Closing Thoughts

Imagine you’re back in that Silk Road café. Gurdjieff stirs his tea, eyes locked on you. “You can live your life asleep,” he says, “or you can wake up. But waking up is work. Hard work.”

Ouspensky scribbles it down for you, maybe softening the edges. You drink your tea and feel the first stirrings of that work, not in a monastery, not on a mountaintop, but here, in your own life, right now.

Because the Fourth Way doesn’t care where you are. It only cares whether you’re awake.

Comments by The Dapper Savage